Alfred Russel Wallace’s name rings a bell for few people. Yet this British scientist is a man who fundamentally changed science. In the 1850s, the biologist observed the Indonesian fauna and flora. Faced with a fever on the island of Halmahera, he devised the theory of natural selection. He wrote: “It occurred to me to ask the question, why do some die and some live? And the answer was clearly, on the whole the best fitted live.” Wallace further elaborated his idea of natural selection in an essay which he sent to a colleague in London in 1858 with the express request that he read the article thoroughly and assist in its publication. That London colleague, Charles Darwin, was just about to finish his book On the Origin of Species... Two scientists, one on a boat in South America and one on an Indonesian island, came to the same conclusion at about the same time… organisms that are better able to adapt to their environment have a better chance of having descendants that survive.

Wallace and Darwin are not alone. Isaac Newton and Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz independently developed the modern theory of differential calculus in the 17th century. Carl Wilhelm Scheele and Joseph Priestly described the chemical element of oxygen at the same time in the 18th century. In 1876, Elisha Gray and Alexander Graham Bell patented the invention of the telephone at the same time. And Alexander Friedmann and Georges Lemaître independently formulated the Big Bang theory in the 1920s. Platinum, helium, cadmium the periodic table of chemical elements, the steam engine, the polio vaccine, the light bulb, the sound film, the atomic bomb… all simultaneous discoveries and inventions.

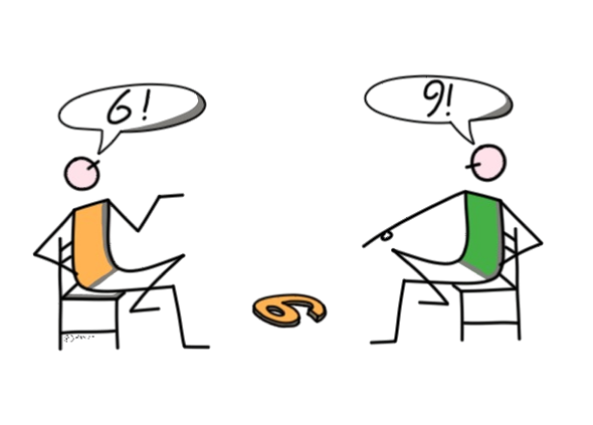

So there can be no doubt. Great minds think alike! Just like you and I sometimes think of the same thing during a conversation, Darwin and Wallace were thinking of natural selection at the same time... Or is this conclusion taken too hastily and other elements are at play? Scientists keep building on previous insights and so these clever guys (and, invariably, a woman like Marie Curie who discovered radioactivity in 1896) are just the right people in the right places at the right time.

…BUT FOOLS SELDOM DIFFER

The quote “Great minds think alike” first appeared at the beginning of the 17th century. It is a humorous expression that is used when two people think alike at the same time and thus suggests that both people must be very intelligent. Less well known is the second half of the quote, “Great minds think alike, but fools seldom differ”. The second part painfully reminds us that people who come to the same conclusion are not so smart after all.

In his book Thinking Fast, Thinking Slow, Daniel Kahneman explores various elements of why our brain often misleads us as in the following situation. A person describes his neighbour as follows: “Steve is very shy and withdrawn, invariably helpful, but with little interest in people or in what is happening in the world. He is gentle and orderly, with a need for structure and regularity and a passion for detail”. Is Steve more of a librarian or a blue-collar worker? Like most people, you probably think that Steve is a librarian because the description fits the characteristics of a bookworm better than that of a blue-collar worker. Except that there are many more blue-collar workers than librarians so the statistical probability that Steve is a blue-collar worker is much higher. Kahneman describes this as the ‘WYSIATI’ rule – ‘What You See Is All There Is’. In order to believe a story, people do not need completeness, but rather consistency and logic.

The Nazi regime’s 1941 decisions to invade the Soviet Union and the US military leadership’s decision not to move the fleet at Pearl Harbor to avoid a Japanese attack, the US fiasco of the Bay of Pigs’ landing in Cuba in 1961, the Watergate scandal in 1972 or the space shuttle Challenger accident in 1986... are all examples of moments where people were convinced by an incomplete and consistent story. They are also well-known examples of what the American psychology professor Irving Janis termed ‘groupthink’ – “The more amiability and esprit de corps there is among the members of a policy-making ingroup, the greater the danger that independent critical thinking will be replaced by groupthink, which is likely to result in irritational and dehumanizing actions directed against outgroups”. Groupthink in itself is not problematic; in the best cases, groupthink allows you to make decisions quickly as a group, to carry out tasks efficiently and to achieve goals. But in the worst cases, groupthink leads to lame analyses, poor decision-making and disastrous outcomes.

Irving Janis identified eight symptoms – flashing lights – that can indicate groupthink. The first two symptoms relate to the group overestimating its power and morality:

- Illusions of invulnerability that create excessive optimism and encourage risk-taking

- Unquestioned belief in the morality of the group causing members to ignore the consequences of their actions

A second group of blinkers indicate isolation and disconnection from reality:

- Rationalising warnings that might challenge the group’s assumptions

- Stereotyping opponents of the group as weak, bad, prejudiced, spiteful, impotent or stupid

And a final group of symptoms point to peer pressure:

- Self-censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus

- Illusions of unanimity among group members, silence being seen as consent

- Direct pressure to conform is applied to any member who questions the group, expressed in terms of ‘disloyalty’

- Brainwashing – self-appointed members who shield the group from dissenting information

An important task for each group member is to recognise these symptoms in time and to alert the others to the dangers. But an even more important task is to install a culture in the group that allows everyone to think freely and critically without being punished by the group.

THE BOSS ISN’T ALWAYS RIGHT

On Thursday 25 January 1990, an Avianca Boeing 707 flew from the Colombian capital Bogota to New York. The weather over the Big Apple was extremely bad, which led to many delays. Air traffic control ordered the pilots to circle above New York for more than an hour before landing. After half-an-hour, the control tower contacted the plane again and the pilots reported in full panic that, due to a shortage of fuel, they could only keep the plane in the air for another five minutes. Due to poor visibility, a few minutes later a first emergency landing failed. Subsequently, two engines failed and the Boeing 707 crashed at 21.34 near Nevak, 30 kilometres from the airport. Seventy three of the 158 passengers did not survive the crash. According to a number of experts interviewed by Canadian author Malcolm Gladwell for his book Outliers, the cause of the disaster is clear… poor communication between the pilots and their fear of going against orders from the airport control tower. “The failure of the flight crew to adequately manage the airplane’s fuel load and their failure to communicate an emergency fuel situation to air traffic control before fuel exhaustion occurred” read the experts’ report after the accident. Gladwell concludes that many plane crashes are the result of culture and communication. According to him, the most important aspect of aircraft safety is not the equipment, but how pilots communicate and deal with hierarchy. If pilots communicate openly, clearly and honestly, they can greatly reduce the risk of a crash. But this kind of open communication is only possible if the internal culture between the pilots and within the airline allows it.

In the American consulting firm McKinsey, this principle is called ‘the obligation to dissent’. Marvin Bower, the father of modern consulting, installed this principle in his consulting firm after a brief encounter with Fred Gluck. Gluck was an ordinary consultant for the firm and, when Bower happened to ask him how Gluck’s project was going, he answered bluntly “bad”. The next day, Gluck received a note from Bower with some words of thanks. Gluck’s honesty had enabled Bower to intervene and adjust the project. From then on, Bower cultivated the principle of contradiction. It means that the youngest, most junior person in a given meeting can totally disagree with the most senior person in the room without any concern.

Create an open culture by being curious, listening and asking questions, allow different views in a debate and talk to each other until the best solution is found... I fully agree with the consultancy guru Marvin Bower. And so you see... Great minds think alike!